OptiPrepTM多功能分离液是质量浓度为60%(w/v)的碘克砂醇溶液,密度为1.32 g/mL。

OptiPrepTM应⽤手册C26“基于密度梯度纯化肝⾮实质细胞”⽐较了⼀些纯化这些细胞的⽅法。

OptiPrepTM Reference List RC07“肝和胰腺星状细胞”中提供了一个所有使用OptiPrepTM多功能分离液已发表论文的全面参考书目:https://diagnostic.serumwerk.com/references-2/cell-references-serumwerk/。

如需获取文本中提到的其他应用手册,http://www.shanjin.com.cn/news/3.html,页面按数字即可进行查询。

1.背景

肝星状细胞占肝细胞总数的15%,其转化为肌成纤维细胞样细胞的能力被认为是肝纤维化的关键事件。因此,⼈们对这些细胞的分离有相当⼤的临床研究兴趣;继⾎液⽩细胞和树突状细胞之后,它们可能是哺乳动物细胞中研究最⼴泛的细胞。星状细胞(有时称为脂肪储存细胞/fat-storing或 Ito)是⾮实质细胞 (NPC) 中密度最低的细胞,与其他 NPC(枯否细胞/Kupffer cells和内⽪细胞/endothelial cells)不同,它们可以使⽤简单的单密度梯度或两步不连续梯度有效纯化⾄90-95%的纯度。两步不连续梯度⼴泛⽤于需要纯化星状细胞和枯否细胞的研究,并在应⽤手册C26中进⾏了描述。胰腺星状细胞也在慢性胰腺炎中介导纤维化,并且也是组织中密度最⼩的细胞;因此,在它们的分离纯化中使⽤了⾮常相似的梯度策略。

2. 细胞悬液的制备

本应⽤手册中的详细⽅法仅限于密度梯度分离;制备组织细胞消化物的⽅法可能在实验室中已经很成熟,仅总结如下。

2a.肝脏消化

通常使⽤组织灌注系统通过胶原酶消化肝脏来制备实质细胞。然后通过50g差速离心沉降1-4分钟将这些细胞与⾮实质细胞分离。虽然可以从50g中的上清液分离出⾮实质细胞,但产率通常较低。最⼴泛使⽤的步骤是⽤胶原酶和链霉蛋⽩酶或肠毒素的混合物灌注肝脏,以选择性地破坏实质细胞[1,2]。

2b.胰腺消化

胰腺细胞悬浮液的制备遵循更传统的⽅法,即⽤链霉蛋⽩酶和胶原酶在37°C下消化解剖并切碎的组织30分钟,然后通过不锈钢⽹上的尼⻰过滤 [3]。

2c.细胞悬浮液

通常将细胞从粗悬浮液中沉淀出来,并在密度梯度分离之前洗涤⼀次或两次,以除去任何残留的酶和/或内毒素。还可以添加脱氧核糖核酸酶 I /DNS I酶来降解受损细胞释放的任何DNA,否则会导致细胞聚集。将细胞悬浮在等渗盐溶液中;通⽤溶液,如 Hanks 平衡盐溶液 (HBSS)(如果需要,可添加Ca2+)或配制的溶液:Gey’s 平衡盐溶液 (GBSS) 通常⽤于肝细胞。

3. 梯度选择

Nycodenz®

自1986年以来,Nycodenz®被⼴泛⽤于肝星状细胞的纯化。最简单的⽅法之⼀由 Schäfer 等⼈于 1987 年⾸次描述 [4],其中包括将 28.7% (w/v) Nycodenz®的等渗溶液添加到 NPC 悬浮液中,以将其密度提⾼到约1.072克/毫升(13.2% Nycodenz)。在顶部铺上⼀层平衡盐溶液,离⼼后从界⾯上⽅回收星状细胞。随后Gressner 和Zerbe [5] 将密度降低⾄约 1.049 g/ml (8.2% Nycodenz) 以提⾼纯度,后者已被⼴泛使⽤(例如参考⽂献6-9)。细胞悬液中Nycodenz的最终浓度也可能⾼达 14.35% [10]。在某些情况下,NPC 细胞悬液会铺在 Nycodenz溶液之上,可能是 13% [11]、9% [12] 或 8.2% [13]。在少数情况下,粗细胞悬浮液会铺在8.2% 和 15.6 % (w/v) Nycodenz [14,15] 的不连续梯度上面,但这种梯度形式通常⽤于星状细胞和枯否细胞的同时分离纯化。

使⽤ Nycodenz 纯化胰腺星状细胞⼏乎完全按照肝细胞的⽅法进⾏ [4,5],并由 Apte 等⼈⾸次描述 [16]。通常,将粗细胞悬浮液调节⾄的浓度约为 11.4% (w/v) [例如参考⽂献 16-19],但也有⼀些变化:12% [20]、13.2% [21] 和 15.1% [22]。

OptiPrepTM

自 1998 年以来,OptiPrepTM也被⽤于从肝脏和胰腺中分离星状细胞; Bachem 等⼈ [23] 发表了第⼀篇论⽂,其中细胞悬浮液被铺在单密度屏障上,Peterson 和 Rowden [24] 使⽤ 5%、10%、20% 和 25% 碘克沙醇/iodixanol的多层不连续梯度。将 NPC 悬浮液的密度调整到略⾼于星状细胞的密度的策略(如 Nycodenz)也变得流⾏。与 Nycodenz⼀样,溶液的最终密度也趋于降低,低⾄ 1.045 g/ml(相当于 7.2% w/v 的碘克沙醇浓度)的例子已经被报道[3]。

4. ⽅法选择

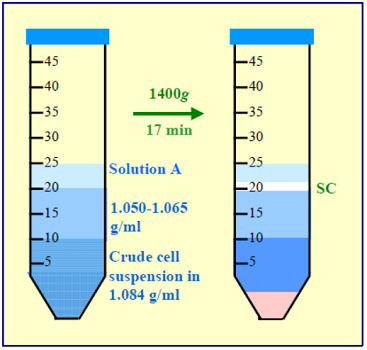

由于 OptiPrep 易于使⽤,以下⽅法基于该试剂的使⽤。然⽽,第 7 部分给出了合适的 Nycodenz 原液的制备及其使⽤。仅给出了漂浮策略,因为这是从主要密度较⼤的混合物中分离出密度最⼩颗粒的成熟⽅法。策略 B 中给出了常规漂浮⽅法(策略 A)的⼀种变体,其中低密度梯度溶液铺在调整到 1.084 g/ml 的 NPC 悬浮液上(⻅图 1 和 2)。

策略B是⾸选策略,因为星状细胞通过“⼲净”的分离层与样品分离; 因此,它们与较致密的细胞和任何残留的可溶性成分(例如消化酶和破碎细胞释放的任何细胞质物质)完全分离。该策略⼴泛⽤于从⼩⿏脾脏、胸腺和淋巴结中纯化胰岛和树突状细胞。

以下⽅法参考自参考⽂献 2 和 3。

5. 所需溶液

- Gey’s 平衡盐溶液 (GBSS) 或 Hank 平衡盐溶液,含或不含Ca2+/Mg2+ (参⻅注释 1)。

- OptiPrep(使⽤前轻轻摇晃瓶⼦)

- 碘克沙醇 (40% (w/v)) ⼯作溶液:混合 4 体积溶液B和 2 体积溶液A(⻅注释2)。

6. 实验⽅案

所有操作均在 4°C 下进⾏。

6a.策略 A

- 将溶液C 与溶液 A 混合,使碘克沙醇的最终浓度为 8.0-11.5% (w/v) 碘克沙醇溶液 ( ρ = 1.050-1.065 g/ml),并⽤此悬浮最终洗涤的细胞沉淀。或者将细胞悬浮在溶液 A 中并与溶液 C 混合以产⽣ 8.0-11.5% 碘克沙醇悬浮液(参⻅注释 3)。

- 将 10-20 ml 转移⾄离⼼管中,并在顶部铺上 8-10 ml 溶液 A(参⻅注释 4)。

- 1400 g 离⼼ 15-20 分钟;允许转⼦在没有制动器的情况下减速(参⻅注释 5)。

- 收集位于溶液 A 和样品之间界⾯处的细胞(⻅图 1)。

6b.策略 B

- 将溶液 C 与溶液 A 混合,使碘克沙醇的最终浓度为 15% (w/v) 碘克沙醇溶液 ( ρ = 1.084 g/ml),并⽤其悬浮最终洗涤的细胞沉淀(参⻅注释 6 和7).

- ⽤溶液 A 稀释溶液 C,得到含有 8.0-11.5% (w/v) 碘克沙醇的溶液 ( ρ =1.050-1.065 g/ml)(⻅注释3)。

- 将 5-10 ml 该溶液铺在相同体积的细胞悬液(15% 碘克沙醇溶液)上;然后在顶部铺上约 5 ml 溶液 A(参⻅注释 8)。

- 1400 g 离⼼ 15-20 分钟;允许转⼦在没有制动器的情况下减速(参⻅注释 5)。

- 收集在溶液 A 和低密度屏障之间的界⾯处带状的细胞(参⻅图 2)。

7. 注释

- 可以使⽤与细胞相适用的任何培养基。有关制备溶液的更多信息参考:细胞应⽤手册 C01。

- Nycodenz 基础溶液:配制不含 NaCl 的溶液 A。将 50 毫升该溶液放入 150 毫升烧杯中,置于加热磁力搅拌器上,温度设置为约 50°C,并添加 28.7 g Nycodenz粉末直⾄溶解。让溶液冷却⾄室温,然后⽤溶液 A(去除了 NaCl)定容⾄ 100 ml。如果需要,过滤除菌。⽤溶液 A(完全)稀释,产⽣与策略 A 或 B 中描述的碘克沙醇溶液浓度相同的溶液。

- 使⽤能够提供最佳星状细胞回收率和纯度的碘克沙醇(或 Nycodenz)浓度。

- 或者使⽤注射器和⾦属插管将细胞悬浮液铺在溶液 A 下。

- 使⽤制动器会导致液体中形成涡流并混合内容物。

- 该细胞层的实际密度并不是特别关键,只要足够密即可支持低密度解决⽅案。

- Brouwer等⼈[2]等⼈描述的两层法中,将细胞悬液置于在低密度层。

- 或者使⽤注射器和⾦属插管将细胞悬浮液分层在较低密度的溶液下。

相关产品

| 产品名称 | 品牌 | 包装规格 | 货号 | 货期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nycodenz | Serumwerk Bernburg AG | 25G | 18003-25G | 现货 |

| 50G | 18003-50G | 现货 | ||

| 100G | 18003-100G | 现货 | ||

| 500G | 18003 | 现货 | ||

| Histodenz | Sigma/西格玛 | 100G | D2158-100G | 3天左右 |

| Optiprep | Serumwerk Bernburg AG | 250ML | 1893 | 现货 |

| OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium | Sigma/西格玛 | 250ML | D1556-250ML | 3天左右 |

| Optiprep | STEMCELL | 250ML | 07820 | 3天左右 |

8. 参考⽂献

- Boyum, A., Berg, T. and Blomhoff, R. (1983) Fractionation of mammalian cells In Iodinated density gradient media – a practical approach (ed. Rickwood, D.) IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 147-171

- Brouwer, A., Hendricks, H. F. J., Ford, T. and Knook, D. L. (1991) Centrifugation separations of mammalian cells In Preparative centrifugation – a practical approach (ed. Rickwood, D.) IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 271-314

- Shek, F. W-T., Benyon, R. C., Walker, F. M., McCrudden, P. R., Pender, S. L. F., Williams, E. J., Johnson, P. A.,Johnson, C. D., Bateman, A. C., Fine, D. R. and Iredale, J. P. (2002) Expression of transforming growth factor-ß1 by pancreatic stellate cells and its implications for matrix secretion and turnover in chronic pancreatitis Am. J. Pathol., 160, 1787-1798

- Schafer, S., Zerbe, O. and Gressner, A.M. (1987) The synthesis of proteoglycans in fat-storing cells of rat liver Hepatology, 7, 680-687

- Gressner A.M. and Zerbe, O. (1987) Kupffer cell-mediated induction of synthesis and secretion of proteoglycans by rat liver fat-storing cells in culture J. Hepatol., 5, 299-310

- Zhang, L.P., Takahara, T., Yata, Y., Furui, K., Jin, B., Kawada, N. and Watanabe, A. (1999) Increased expression of plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor during liver fibrogenesis of rats: role of stellate cells J.Hepatol., 31, 703-711

- Arias, M., Lahme, B., Van de Leur, E., Gressner, A.M. and Weiskirchen, R. (2002) Adenoviral delivery of an antisense RNA complementary to the 3’ coding sequence of transforming growth factor-ß1 inhibits fibrogenic activities of hepatic stellate cells Cell Growth Differ., 13, 265-273

- Kurikawa, N., Suga, M., Kuroda, S., Yamada, K. and Ishikawa, H. (2003) An angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist,olmesartan medoxomil, improves experimental liver fibrosis by suppression of proliferation and collagen synthesis in activated hepatic stellate cells Br. J. Pharmacol., 139, 1085-1094

- Yoshiji, H., Kuriyama, S., Noguchi, R., Yoshii, J., Ikenaka, Y., Yanase, K., Namisaki, T., Kitade, M., Yamazaki, M.,Tsujinoue, H. and Fukui, H. (2005) Combination of interferon-ß and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor,perindopril, attenuates the murine liver fibrosis development Liver Int., 25, 153-161

- Paradis, V. Scoazec, J.W., Kollinger, M., Holstege, A., Moreau, A., Feldmann, G. and Bedossa, P. 1996) Cellular and subcellular localization of acetaldehyde-protein adducts in liver biopsies from alcoholic patients J. Histochem. Cytochem., 44, 1051-1057

- Nakamura, T., Arii, S., Monden, Z., Furutani, M., Takeda, Y., Imamura, M., Tominaga, M. and Okada, Y. (1998) Expression of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger emerges in hepatic stellate cells after activation in association with liver fibrosis Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 5389-5394

- Bataller, R., Sancho-Bru, P., Ginès, P., Lora, J.M., Al-Garawi, A., Solé, M., Colmenero, J., Nicolás, J.M., Jiménez, W., Weich, N., Gutiérrez–Ramos, J-C., Arroyo, V. and Rodés, J. (2003) Activated human hepatic stellate cells express the rennin-angiotensin system and synthesize angiotensin II Gastroenterology, 125, 117-125

- Horani, A. Muhanna, N., Pappo, O., Melhem, A., Alvarez, C.E., Doron, S., Wehbi, W., Dimitrios, K., Friedman, S.L. and Safadi, R. (2007) Beneficial effect of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) on immune modulation of experimental hepatic fibrosis Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., 292, G628-G638

- Shafiei, M.S. and Rockey, D.C. (2006) The role of integrin-linked kinase in liver wound healing J. Biol. Chem., 281, 24863-24872

- Novosyadlyy, R., Dudas, J., Pannem, R., Ramadori, G. and Scharf, J-G. (2006) Crosstalk between PDGF and IGF-I receptors in rat liver myofibroblasts: implication for liver fibrogenesis Lab. Invest., 86, 710-723

- Apte, M.V., Haber, P.S., Applegate, T.L., Norton, I.D., McCaughan, G.W., Korsten, M.A., Pirola, R.C. and Wilson, J.S. (1998) Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture Gut, 43, 128-133

- Masamune, A., Kikuta, K., Satoh, M., Satoh, A. and Shimosegawa, T. (2002) Alcohol activates activator protein-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases in rat pancreatic stellate cells J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 302, 36-42

- Phillips, P.A., McCarroll, J.A., Park, S., Wu, M-J., Pirola, R., Korsten, M., Wilson, J.S. and Apte, M.V. (2003) Rat pancreatic stellate cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases: implications for extracellular matrix turnover Gut, 52, 275-282

- Shimizu, K., Shiratori, K., Kobayashi, M. and Kawamata, H. (2004) Troglitazone inhibits the progression of chronic pancreatitis and the profibrogenic activity of pancreatic stellate cells via a PPARy-independent mechanism Pancreas,29, 67-74

- Jaster, R., Sparmann, G., Emmrich, J. and Liebe, S. (2002) Extracellular signal regulated kinases are key mediators of mitogenic signals in rat pancreatic stellate cells Gut, 51, 579-5844.1027

- Ohnishi, N., Miyata, T., Ohnishi, H., Yasuda, H., Tamada, K., Ueda, N., Mashima, H. and Sugano, K. (2003) Activin A is an autocrine activator of rat pancreatic stellate cells: potential therapeutic role of follistatin for pancreatic fibrosis Gut, 52, 1487-1493

- Tanioka, H., Mizushima, T., Shirahige, A., Matsushita, K., Ochi, K., Ichimura, M., Matsumura, N., Shinji, T., Tanimoto, M. and Koide, N. (2006) Xanthine oxidase-derived free radicals directly activate rat pancreatic stellate cells J.Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 21, 537-544

- Bachem, M.G., Schneider, E., Groß, H., Weidenbach, H., Schmid, R.M., Menke, A., Siech, M., Beger, H., Grunert, A. and Adler, G. (1998) Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rat and humans Gastroenterology, 115, 421-432

- Peterson, T.C. and Rowden, G. (1998) Drug-metabolizing enzymes in rat liver myofibroblasts Biochem. Pharmacol., 55, 703-708

OptiPrepTM Application Sheet C27; 第9版,2020年1月(有改动)

手机/微信

手机/微信